The construction of the Meltham Branch Line during the 1860s had resulted in the deaths of at least three people — curious all named James: James Phiney, James Mace and James Beaver — along with numerous injuries, which are detailed in a previous blog post.

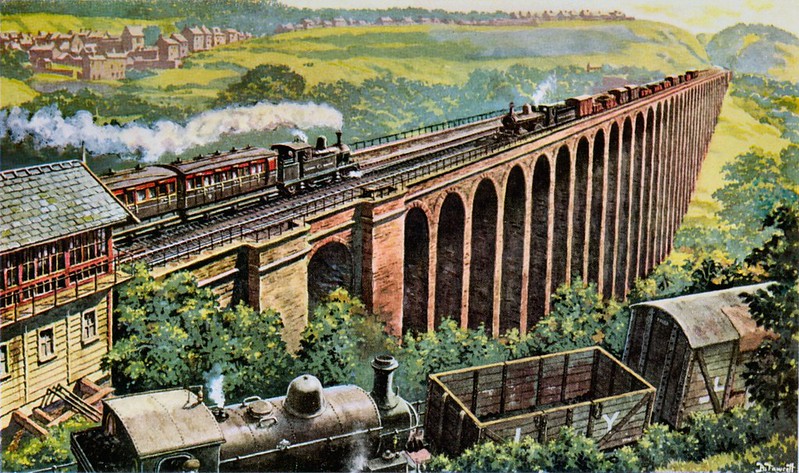

The line initially opened for the transportation of goods in August 1868 but a series of landslips caused to the line to temporarily closed. It wasn’t until inspections in May and June the following year that the line was deemed safe for public transportation and the first passenger service left Huddersfield to Meltham on 5 July 1869.

As to be expected, incidents, accidents, and occasionally deaths, continued to occur over the years and the ones that were found during research for the decades 1870 and 1880 are listed below.

01/Aug/1871: Louis Beecher Furniss

Louis Furniss was a painter who had been employed to do work at the various stations on the Meltham Branch Line, including signs and name boards. On the afternoon of Tuesday 1 August 1871, he boarded the Meltham train at Netherton, entering the carriage closest to the engine. En route to Meltham, he leaned out of the carriage door window and struck up a conversation with the train driver. It was unknown if Furniss, who possessed a door key, had unlocked the carriage door or if it hadn’t been secured properly, but it suddenly swung open and he fell out — fortunately, he landed and rolled away from the track rather than falling under the train.

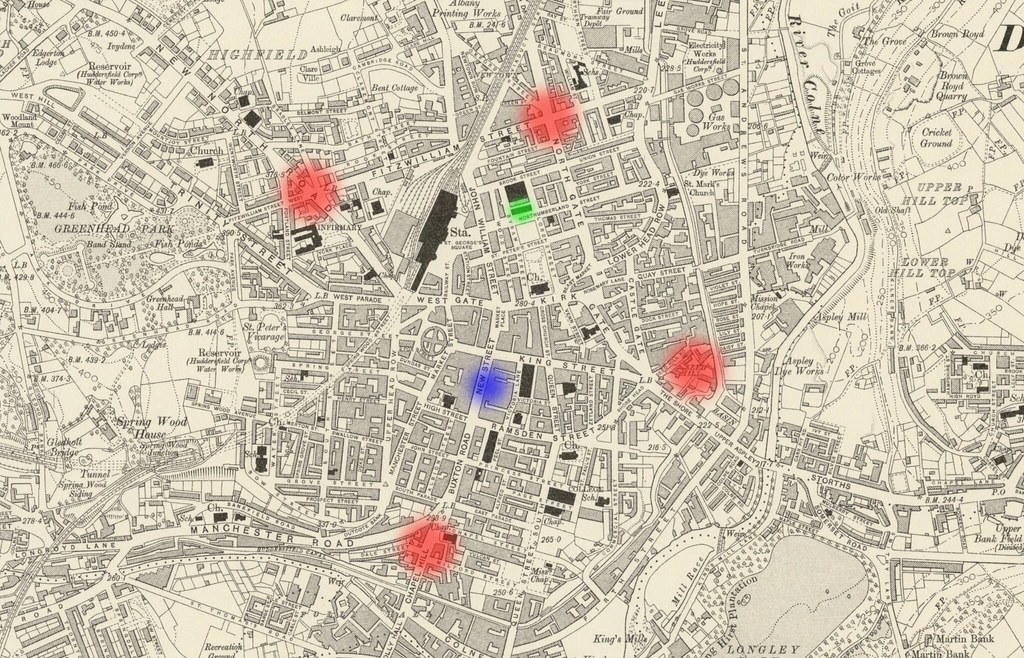

Alerted by the shouts of his fellow passengers, the driver applied the brakes. Furniss was carried unconscious back to the train and laid out on the floor of a first-class carriage. The train, presumably after allowing passengers to get out at Meltham Station, returned to Huddersfield where Louis was taken to Huddersfield Infirmary and his head injuries (described as “severe”) were attended to.1

Louis Beecher Furniss was born in 1849 in Bradford. He married Mary Quinn in 1871 in Huddersfield and they raised a family of four children. He died in 1912, aged 62.

03/Jun/1875: Samuel Mellor Johnson

According to a few sources, Samuel Mellor Johnson was riding a horse along the Netherton to Meltham turnpike when his horse was spooked by a train passing over the road bridge and he was thrown off and killed. As a result, the approaches the bridge were fenced in.

However, I could find no newspaper articles to confirm this story and there are no death registry entries in Huddersfield for anyone with that (or a similar) name in 1875.

04/Jan/1876: E. Schofield

Reported in the Railway Accidents 1876: Return of Accidents and Casualties (January-March 1876) that goods guard E. Schofield injured his toes at Meltham Station after a heavy object fell on his foot and that this accident was beyond his control.

26/May/1876: George Wood

Reported in the Railway Accidents 1876: Return of Accidents and Casualties (April-June 1876) that “weigh clerk” George Wood injured his foot at Meltham Station during shunting operations.

21/Jun/1876: T. Beaumont

Reported in the Railway Accidents 1876: Return of Accidents and Casualties (April-June 1876) that labourer T. Beaumont “slipped whilst at work on the Meltham Branch, and sprained his back”.

25/Sep/1876: Benjamin Taylor

33-year-old cotton grinder Benjamin Taylor was injured as he alighted from an evening train at Meltham Station on Monday 25 September 1876. He missed his footing and fell between the platform edge and the train, breaking his leg above the ankle. At first he thought it was just a bad sprain and the fracture wasn’t diagnosed until a couple of days later.2

The 1881 Census lists Taylor as a “cotton card grinder”, married to Mary (born in Linthwaite) and with 7 children. The family were living on Calm Lands, Meltham, at the time. He most likely died in 1898, aged 56.

24/Apr/1877: Elijah Ingram

44-year-old American-born Elijah Ingram3 was a cooper employed by Bentley and Shaw Brewery in Lockwood, who lived in Cowcliffe, Huddersfield. On the evening of Tuesday 24 April 1877, at around 5:55pm, he attempted to cross the railway line at Lockwood Station in order to catch the train from Meltham into Huddersfield but was struck by a goods engine travelling at around 30mph in the other direction. He was flung over 10 yards onto the platform. Bleeding profusely from his head injuries, he was carried to the nearby Railway Hotel where a surgeon named Hall attended to him. Elijah never regained conciousness and died after vomiting a large amount of blood.4

At the inquest into his death, his widow Ann stated that Elijah was not hard of hearing, but sometimes struggled to understand what was being said to him.5 However, he suffered from rheumatism and this affected how quickly he could move.

The driver of the train, Alfred Hinchliffe, told the inquest that he had seen Elijah but that the deceased had his back to the approaching train. Alfred shouted and sounded the train’s whistle, but Elijah had already stepped out onto the line, seemingly unaware, and was hit by the front of the engine. It was also noted that other passengers were near to Elijah but they apparently failed to alert him of his peril.

The jury returned a verdict of “accidental death” and noted that the station employees had taken reasonable precautions to alert passengers that a goods train was due through the station shortly.

One outcome of the tragedy was that the railway company built a subway to join the two platforms at Lockwood Station. Prior to that, passengers on the down line had to cross over the tracks to buy a ticket, before crossing back over again.

19/Nov/1877: William Fletcher

William Fletcher of Outcote Bank, Huddersfield — a painter in the employment of Bagnall & Quarmby of Shipley — was engaged in painting the bridge over the railway line at Meltham Station when the scaffolding he was stood on collapsed. He fell down onto the tracks, sustaining a severe head wound and a spinal fracture. The Huddersfield Daily Chronicle (21/Nov/1877) reported that William was paralysed and there was faint hope of a recovery.

As far as I can see, there were no further newspaper reports about Fletcher and there is no obvious local deaths recorded for that name in 1877. It may be that he was the William Fletcher who was born around 1860 and who died in mid-1878, aged 18. If so, this might help explain the lack of a recorded inquest into his death.

05/Dec/1877: Michael Quinn

Not long after William Fletcher’s accidental fall, Michael Quinn of Holmfirth was employed whitewashing the gable end of the goods warehouse at Meltham Station when the scaffolding he was stood on collapsed. The Chronicle reported that he suffered bruised ribs and that the lime wash, which he had been painting the walls with, had fallen onto his head and splashed his eyes.6

This was most likely the Michael Quinn born around 1851 in Holmfirth, the son of Irish labourer Thomas Quinn and his wife Cecilia.7 By 1871, 20-year-old Michael was working as a plasterer. The lack of an entry for him in the 1881 Census implies that he was the Michael Quinn who died in 1880, aged only 29.

07/Feb/1878: Collision at Huddersfield

At around noon on Thursday 7 February 1878, a Meltham train collided at a low speed with a waggon at Huddersfield Station. The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer reported that Rev. Joshua Richard Jagoe (vicar of Meltham Mills) and Rev. E.C. Green (vicar of Christ Church, Helme) were the most seriously injured of the passengers. The guard on the train sustained a scalp wound.

19/Oct/1879: Collapse of Retaining Wall

At around 9pm, Abraham Taylor, a weaver residing at Delph, heard a “loud rumbling noise” outside. Upon investigation, he found a retaining wall in the cutting situated below the farmhouse of Joseph Brook had collapsed onto the line. Although the ”Huddersfield Daily Chronicle” (21/Oct/1879) reported that the debris “had fallen onto the line behind Woodfield House”, the description actually implies the collapse happened on the section between Butternab Tunnel and Netherton Tunnel, which tallies with the location of Brook’s farmhouse at the place known locally as Delves. The collapse may have been caused by the 8:35pm departure from Meltham passing by the spot.

Taylor sent his son to inform plate layer George Moorhouse, who lived nearby at Netherton Fold. Moorhouse inspected the damage and sent word to the signalman at Meltham Junction not to allow any trains onto the branch line. Within a short time, 22 men had been recruited to help move the debris, which was estimated at 60 tons. Work to clear the line carried on throughout the night by lamp light and necessitated cutting away some of the embankment. By mid-morning, the line was declared safe and the 11:07am departure from Huddersfield was allowed to run to Meltham.8

13/Jan/1880: Derailment

Just before 9am on Tuesday 13 January 1880, a train heading from Meltham to Huddersfield derailed on a set of points at Meltham Junction, Lockwood. Fortunately the driver was proceeding with caution at the time and, despite the train being full of passengers, no-one was injured.

The Manchester Times (17/Jan/1880) reported that:

The engine, instead of running on the down line, passed into a siding, and was on its way towards a luggage train which was standing there, but with which it did not come into contact. The tender and the first carriage left the line and cut up the permanent way for about twenty yards, but the remained of the the train fortunately kept the metals, and the passengers in that portion were not much inconvenienced. The passengers in the third class carriage were greatly terrified, and got out at the earliest possible moment. Though none of them were injured the whole were more or less severely shaken, and were glad to escape from the train.

A team of workmen from Hillhouse were able to repair the damage within a couple of hours and the line was reopened.9

12/Aug/1881: Bradley Jessop

52-year-old plasterer Bradley Jessop, in the employ of William Eastwood Jowett, fell from scaffolding at Meltham Station on Friday 12 August 1881. He suffered a fractured thigh and head wounds, having fallen head-first from a height of 20 feet. Although the initial prognosis looked good for Bradley, he died at 3:45pm on Tuesday 23 August “from exhaustion (the result of the brain injury)” with his wife at his side.10

The inquest into the death was held on 25 August at Huddersfield Infirmary and was chaired by coroner Mr. Barstow. It was heard that Bradley was one of three men whitewashing the inside of the roof of the railway goods station. For no apparent reason, he tumbled off the scaffold — asked to explain what might have happened, the other workmen felt that he may have overreached himself and lost his footing. His widow stated that, before he died, her husband could give no reason as to why he fell. A verdict of “accidental death” was returned by the jury, who felt that no blame could be attached to anyone else.11

Bradley Jessop was born around 1830 near Berry Brow and appears to have been raised by Francis and Esther Jessop.12 He married local woman Ruth Percival, daughter of weaver James Percival, at the parish church in Almondbury on 16 March 1851. The couple settled in Berry Brow and raised a family of four children.

Following her husband’s death, Ruth continued to live in Berry Brow with her children and she died in 1886, aged 65.

Coincidentally, in 1867, Bradley was the foreman in charge of a group of men whitewashing at Spring Gardens Mill, Milnsbridge, when 24-year-old plasterer’s labourer Andrew Flynn fell off his plank and was caught up in the factory’s machinery. He died about 7 hours later of his injuries. The jury at the inquest into the death laid no blame on Bradley and returned a verdict of “accidental death”.13

Details of the incidents prior to 1870 can be found in a previous blog post.

There is one further blog post detailing accidents from 1890 onwards.